MONITORING INSOLVENCIES – RISK BASED CAPITAL

(March 2023)

Besides recommendations on regulatory reform from the

Federal Insurance Office, primary responsibility for overseeing the financial

health of property and casualty insurers rests with the individual states. For

most of their oversight tenure, states established a common benchmark for

measuring an insurer’s status. They used minimal levels of capital and surplus

and these levels varied substantially among the various states. The problem was

that such levels were similar to the approach used with vehicle laws that

establish financial responsibility (F.R.) minimums. In the former, the low

levels of required capital and surplus bore no resemblance to the actual level

of funds insurers needed to meet their financial obligations. In the latter,

the F.R. amount rarely reflected the potential cost of damages or injuries

caused by significant accidents.

Related Article: Financial Responsibility Limits

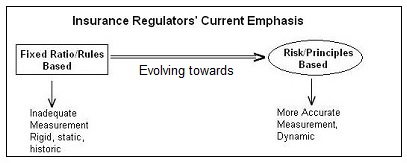

One unintended result of the traditional approach was that

the same mechanism put in place to monitor insurers actually encouraged

companies to assume higher, more hazardous levels of risk. Fortunately, there

is an increasingly used method that more accurately measures an insurer’s vulnerability

to failing to maintain adequate resources. It is called the risk-based capital

concept (RBC).

Traditional

approach vs. RBC

Under RBC, regulators consider the business type and mix

that a given insurer writes. Property-based business is short-tailed and losses

are predictable, so a higher policyholder surplus to premium ratio may be fine.

However, a higher level of long-tailed business means that a lower ratio is

necessary in order to meet possible obligations. Conversely, it also means that

a situation of quick growth calls for quicker action with insurers that write

business with longer tails. Connecting capital requirements to a given

insurer’s appetite for risk resulted in a more effective system of monitoring. As

a simple illustration, consider the following:

|

Example: Scenario One–insurers A, B, C and D write

the same type of business, primarily residential property and casualty. |

||||

|

Insurer |

Policyholder Surplus |

Written Premium |

Evaluation Approach |

|

|

Traditional |

RBC |

|||

|

A |

5,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

Acceptable |

Acceptable |

|

B |

10,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

Acceptable |

Acceptable |

|

C |

3,000,000 |

12,000,000 |

Borderline |

Borderline |

|

D |

3,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

Danger |

Danger |

Under the above circumstance, there’s no difference between

the two approaches. Now let’s make a change in the business mix.

|

Example: Scenario Two–In this situation Insurer A

writes mostly large contractors, B specializes in professional liability while

C and D still write primarily residential property and casualty. |

||||

|

Insurer |

Policyholder Surplus |

Written Premium |

Evaluation Approach |

|

|

Traditional |

RBC |

|||

|

A |

5,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

Acceptable |

Danger |

|

B |

10,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

Acceptable |

Danger |

|

C |

3,000,000 |

12,000,000 |

Borderline |

Borderline |

|

D |

3,000,000 |

15,000,000 |

Danger |

Danger |

Under this situation, the RBC approach would consider the

type of business written, so it would also identify companies A and B as

insurers that should be scrutinized closely while nothing changes under the

older, traditional approach.

|

|

However, RBC Standards do not only consider type or mix of

business, but also evaluates other factors, such as geographic location and

vulnerability to catastrophes.

|

Example: Insurers A and B both write a high amount

of mid-ranged value residences and have the same surplus to premium ratio.

Without any other information, the two companies should be evaluated similarly

using RBC standards. However, that premise changes when it’s known that

Company A operates solely in the Midwest while Company B operates on the

Southeastern Coast. The latter company’s vulnerability to wind loss would

make it subject to closer scrutiny. |

Under RBC Standards, insurers are required to submit their

financial information, including data run through various RBC formulas. RBC

formulas are complex. For illustration’s sake, here is the actual formula used

(provided by the NAIC Website):

P/C Covariance

Calculation = R0 + Square Root of [(R1)2 + (R2)2 + (R3)2 + (R4)2 + (R5)2]

R0: Asset Risk –

Subsidiary Insurance Companies

R1: Asset Risk –

Fixed Income

R2: Asset Risk –

Equity

R3: Asset Risk –

Credit

R4: Underwriting

Risk – Reserves

R5: Underwriting

Risk – Net Written Premium

Another name for the P/C Covariance Calculation is the

Authorized Control Level of risk-based capital calculation or ACL. The ACL acts

as an appropriate benchmark of minimum capital that reflects a given company’s

level of existing operating risk. In other words, this amount represents the

minimal amount of operating capital an insurer must have in order to maintain

operations at its current level of operating risk.

The significance of a company’s ACL is the relationship

between it and a company’s Total Adjusted Capital (TAC). The TAC consists of a

given company’s average, historical financial data.

Regulators can monitor insurers by comparing a company’s

Total Adjusted Capital with the Authorized Control Level. Regulators can act,

suggested by the relationship that exists between those figures, at the time a

financial picture is snapped.

The following table displays what action should be taken

according to the relationship.

|

Total Adjusted Capital (T.A.C.) vs.

Authorized Control Level (ACL) |

Appropriate Action Step |

|

T.A.C. is greater than 200% of ACL |

No Action |

|

T.A.C. equals 150% to 200% of ACL |

Insurer must prepare a report identifying company’s

financial condition including possible corrective action |

|

T.A.C. equals 100% to 150% of ACL |

Regulator requires an insurer to file an action plan

combined with regulator performing audits and exams of the insurer |

|

T.A.C. equals 70% to 100% of ACL |

Regulator acquires authorization to take control of the

insurer, implementing its own action plan, ideally to assure solvency |

|

T.A.C. is less than 70% of ACL |

Regulator is mandated to take control of insurer, usually

involves a technically insolvent insurer |

|

Example: A

state regulator is examining an insurer that, two years earlier, expanded

into a new line of business. It determines an ACL of $187 million dollars.

Studying the last five years of financial data, the regulator develops a

T.A.C. of $423 million dollars. Since the T.A.C. is well over 200% of its ACL,

the insurer is in excellent operating condition. |

While the use of RBC does not guarantee the identification

of every dangerous situation, it does substantially increase the effectiveness

of monitoring solvency and assisting with earlier, corrective action that might

avert permanent impairment.